An AI Agent that Solves Text Games

I created an agent to play text-based games

Text-Based Games

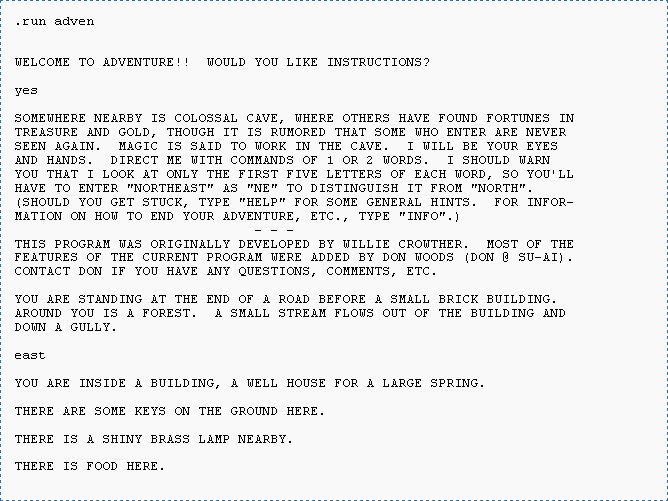

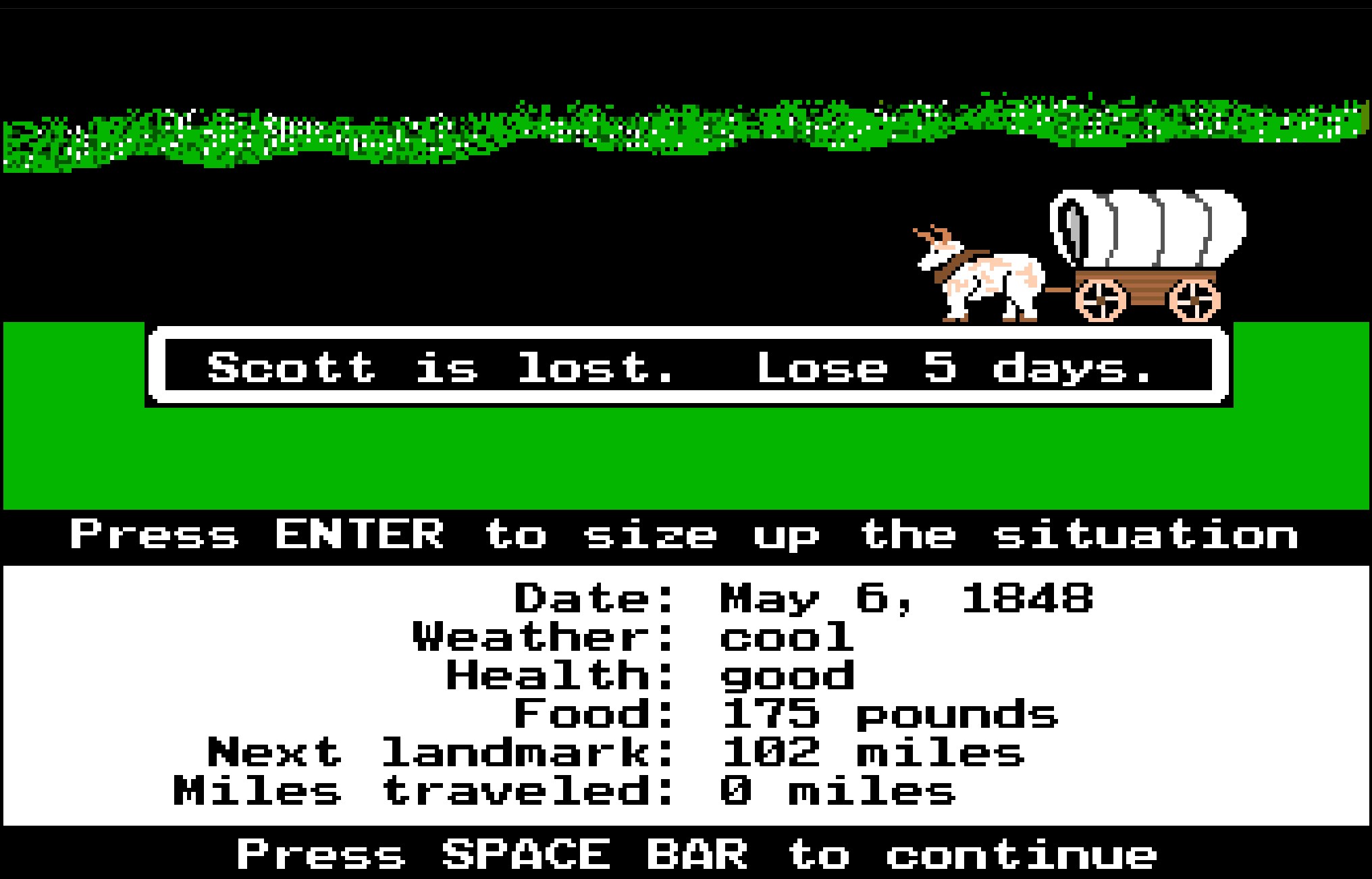

Back in the day, video games didn't have any images at all. Old computers couldn't display graphics, just text. Designed for these computers, games like the Oregon Trail and Colossal Cave Adventure were played without needing any graphics. Players would read what was happening and type in what they wanted to do.

These games were popular in the 1970s and 1980s until they were usurped by games with graphics. We play pretty much every game these days with graphics. Some text-based games added basic graphics to try and compete, but this didn't work. Text-based adventure games are now a small niche interest.

Class

This semester, I took my (hopefully) last class of my PhD. It was really fun, and gave me a lot of flexibility to do some fun and cool projects that didn't quite rise to the level of research. This clas was responsible for my Magic Card Generator and my Bible Semantic Search tool. For my final project, I wanted to do something fairly original and interesting. I decided to train a little agent to solve basic text-based puzzles like the adventure games of yesterday.

Text-Based Agents

Why is this project interesting to me? The short answer is because of LLMs. LLM companies are launching LLM agents - LLMS set up to do things on people's behalf (order food, book a flight, etc). LLMs interact with the world fully through text. To an LLM, acting in the real world via an agentic framework is functionally identical to playing a game in a simulated environment. It doesn't know the difference.

This means that training an LLM to interact with any text-based world (even a simplistic one), is directly applicable to teaching an LLM to interact with the real world!

Teaching an LLM to Navigate a Task-Oriented Environment

How do we even go about training our model to solve basic simulated environments like this? One possible approach is Reinforcement Learning, where we sort of 'set the model loose' in the environment and let it learn from its mistakes.

(I did a fun RL project for a class a couple of years ago. Read about it if you want to learn more about RL)

RL is very computationally costly, though. The RL agent needs to make thousands (or even millions) of mistakes before learning how to perform a task.

There is a tactic that is fairly similar to RL called Behavioral Cloning. With Behavioral Cloning, instead of letting the model make a bunch of mistakes, we show it a bunch of examples of correct behavior. Then, the model gets a pretty good idea of how to behave without ever having to make a mistake itself. Behavioral cloning has been demonstrated to be highly effective on a variety of tasks.

If I wanted to do behavioral cloning, I needed a bunch of examples of correct solutions to text-based adventure games. With that, I could fine-tune a model to act in text environments.

The Environment

So I knew what I wanted to do, but I needed a couple of things:

- I needed a bunch of training data for our agent to behaviorally clone.

- I needed some simple text-based adventures to test the trained agent.

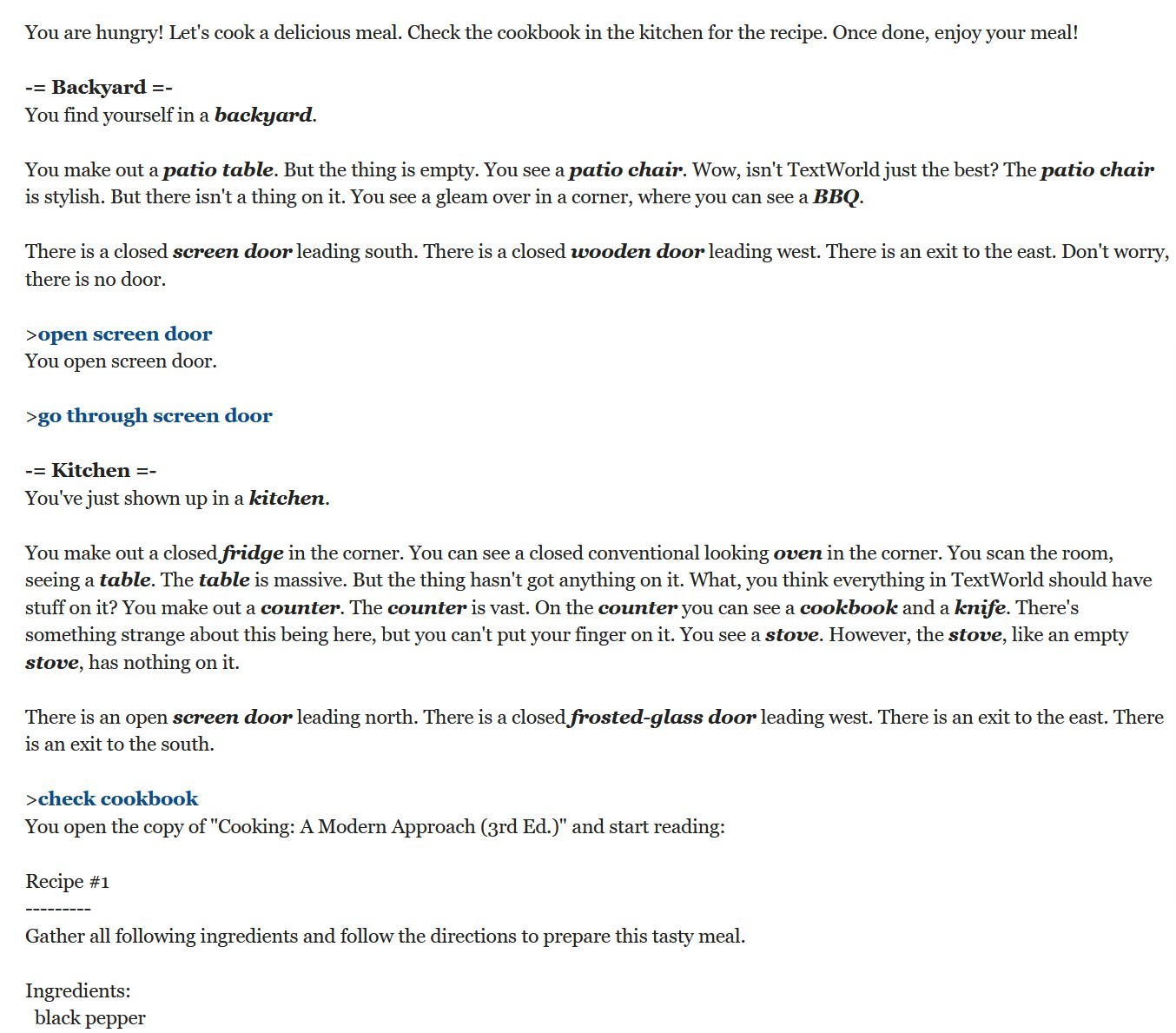

Luckily, I found an answer to this, Microsoft's TextWorld. This is a system created in 2019 that can programatically generate infinite small text-based puzzles.

You can Try it out on the Microsoft Website if you wish.

TextWorld lets you programatically generate as many novel games as you want. I started by generating 10,000 games. For each game I also generated a perfect solution for the agent to learn from.

But what if training on only good examples isn't the best strategy? Training only on perfect games gives the agent a ton of examples of correct things to do. This is great until the model makes a mistake. Then what? It's never seen an example of fixing its own mistake before, and might not know what to do.

In an attempt to make my agent more robust, I created two training datasets. The first one had only perfect solutions. In the second, I generated half perfect solutions and half imperfect solutions. In the imperfect games, the agent periodically takes incorrect actions and then has to backtrack, fixing the issue. This way (hopefully), the model learns how to fix its mistakes and not get stuck.

It was a huge hassle to generate this data. Even though Microsoft wrote the TextWorld framework, it won't run on Windows. I had to use WSL, the Windows Subsystem for Linux. This lets me automatically run a Linux virtual machine on my Windows machine. Within WSL, I created a python virtual environment, running on the Linux virtual machine. Getting that all set up was a lot of work.

I needed to get the training data into a form the agent could handle and do well with. What this involved was giving my model a history of everything it has done so far, including its objective, a history of places it had been (states) and a history of actions it had taken. I used special tokens, [S] and [A] to help the model learn its previous states and actions.

One other consideration I took while generating the data was making the examples vary in difficulty. I didn't want the agent to learn weird heuristics like, "I will always be done in 10 steps" (We'd worry about that if every example was 10 steps long). To get around that, I generated examples with more or less rooms, with more or less steps, or with more or less items in the rooms. This way, I hoped to train a more robust, generalizable agent.

Finally, I set my laptop to chug all night, generating 10,000 games of training data and 100 test games, each with their solutions.

Training the Model

With all of my data ready, I was ready to train a model. The first thing I needed to do was select which model I would be fine-tuning. Thankfully, smallish Language Models have been getting super smart the last few years. Today's small models (a couple billion parameters) perform comparably to earlier models like GPT-3, which were much larger (175 billion parameters). I decided to fine-tune a recently-released Qwen model, Qwen 2.5 0.5B (Qwen is a Chinese company that publishes open-weight models).

Why did I choose that model? The most important factor is the size of model's context window. A model's context window is how many tokens (words) it can 'remember' at any given time. The reason this is important is that we need our agent's memory to be long enough to remember its objective and everything it has done so far. If I were to fine-tune GPT-2 like I did earlier this year, it wouldn't have a long enough context window to remember everything it's done and solve more complicated puzzles. Choosing a small Qwen model gives the agent a long enough memory to succeed.

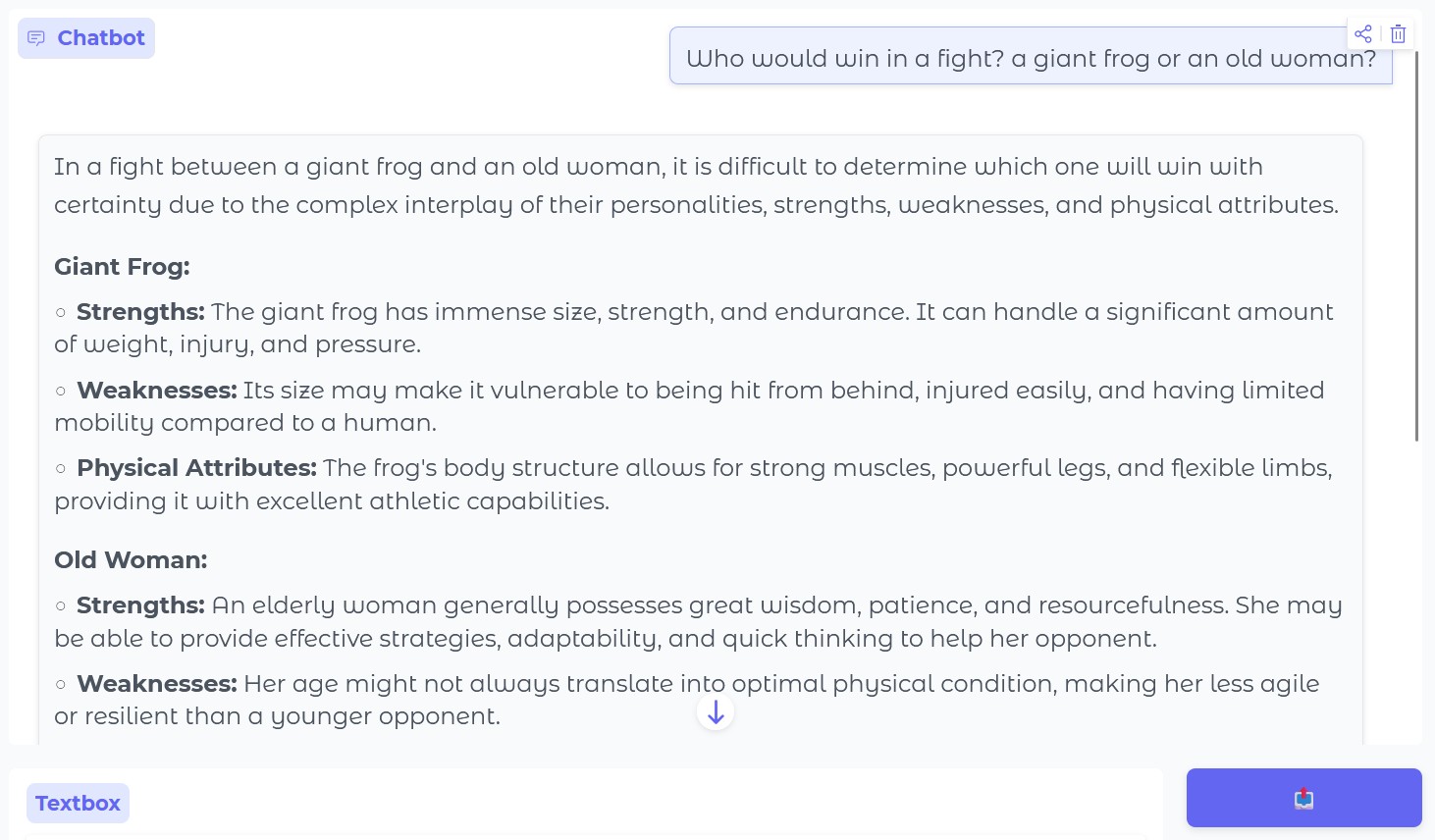

Qwen 2.5 0.5B is distilled from a larger model. This technique involves training a model to match the outputs of a larger, smarter model instead of training it from scratch. This method is very effective. To test how smart the model was before fine-tuning it, I asked it one of my favorite LLM testing questions, "Who would win in a fight, an old woman or a giant frog?" While this is a silly question, I think it's great. It is unlikely to appear often in the model's training data, so we get to see its ability to reason about something it hasn't seen before.

One notable feature of choosing such a small model is that it is able to run on a normal computer. While frontier models like Gemini and ChatGPT require specialized hardware to run, Qwen 2.5 0.5B can be run on the average laptop. (You're probably thinking, 'but I use GhatGPT on my laptop' - not really. When you use ChatGPT or other models, the model is actually being run in some data center somewhere.)

The details of training aren't very interesting, so I'm not going too deep into it. At a high level, I showed the model lots of examples (over 60,000) of turns in TextWorld games, and had it 'guess' what action it should take. I then showed it what the correct action it should have taken, letting it learn. I did this using TRL (Transformers Reinforcement Learning), which handled a lot of the data formatting for me. Using both the only-correct dataset and the dataset with small mistakes, I trained two versions of the agent.

Since I was creating a little agent, I decided to name him and use Gemini 3 Pro Image (Nano Banana) to generate a little picture of my text agent. I named him Pip. This is purely cosmetic, but it makes the agent feel more real.

Testing the Model

Now was the moment of truth: Would Pip be able to solve these text-based puzzles?

To test him out, I spun up both a TextWorld environment, and had Pip try to solve the 100 test games I had generated earlier. The agent trained on only perfect solutions correctly solved 97 of the games! The agent trained on solutions with intermittent mistakes solved 94 of them. Both of those were A-level performance.

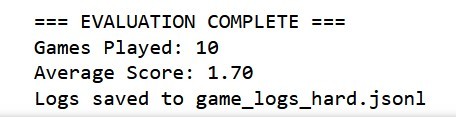

I decided to do a challenge round of testing. All of the training and test example games I had generated were simple, linear quests. The agent was given a single objective and the steps to carry it out, and it could do that. However, TextWorld allows you to generate games with multiple objectives/sub-quests. These take a really long time to create, so I wasn't able to include any of those in my training data. I did take some time to generate 10 'challenge' environments with two objectives.

This was the real test of Pip's intelligence. Because he never saw a multi-objective environment while being trained, I wasn't sure if he would be able to solve any of the challenge games. Of the 10 challenge rounds, Pip solved the first objective in all 10, and the second objective in 7, giving him an 85%. Not bad for something he was never trained to do!

Conclusion

I thought this project was pretty cool. I was able to train a little agent to solve text-based environments. It was really exciting that even though the environment is simplified, my agent successfully navigated the environment and carried out the tasks it needed to do. However, there are some limitations.

The tasks Pip learned to carry out are all fairly linear. The agent needs to do step A, then step B, then step C, etc. TextWorld tells the agent what it needs to do in a fair amount of detail. This means Pip never learned to make its own plans, just to follow the instructions TextWorld gave it. This isn't necessarily a bad thing - creating an agent that can follow instructions is still really cool.

In spite of these limitations, I'm very happy with my little agent. The model is very capable while still being small enough to run on a normal household computer.