Finishing Prismo

Making a video game is hard work.

Finishing Projects

Between 90 and 95% of construction projects take longer than estimated, go over budget, or both. source, source 2 Construction projects tend to cost between 30-80% more than initially estimated, source and can take between 30% to 500% longer than initially estimated. source

I had the same experience while trying to finish my video game, Prismo. In my last post about the game, I promised it would be done by the end of 2024.

It was not.

So what happened?

I started working on Prismo in early 2023. While working on Chrono Chaos, I decided to make a 2-D platformer game. I worked on it off and on through 2023, with a goal to finish it by the end of that year.

After 9 months of work, I got a decent character controller, player animation, and physics system made with no levels and barely any plot ideas. Like an over-budget construction project, I had to redo my estimate. I set a goal at the begining of 2024 to finish the game by the end of that year.

I didn't realize everything that goes into making a game all by yourself.

Things You Don't Consider

So many things go into creating a video game, especially if you don't want to use someone else's art. You need to make a controller for the character where movement feels natural. You need to create a piece of art for every object and every character in the game. Enemies need a program to control them. You need to create music and sound effects. You need to create and program a user interface, pause menu, volume control, and a thousand other little things to make the game playable. Once you know where you intend to publish the game you have to ensure compatability with different platforms, add touch controls for mobile devices, and optimize quality settings. At every step, you need to test your changes and make sure everything works together in harmony.

And that's just the mechanics of the game. If you want your game to be fun, you need to learn and follow principles of good game design. You need your game to be fun and somewhat challenging without being too hard. You need your controls to be intuitive. The environment should help point the player in the right direction without giving things away. The game also needs a compelling story to get the player invested in the character.

I learned about all of these firsthand as I slogged through the multi-year process of creating Prismo. While I could write a many-post series on game design and the process of creating prismo, that would be a lot of work for me and I doubt anyone would read it. Instead, I'll just discuss a few aspects of the game creation process.

Story

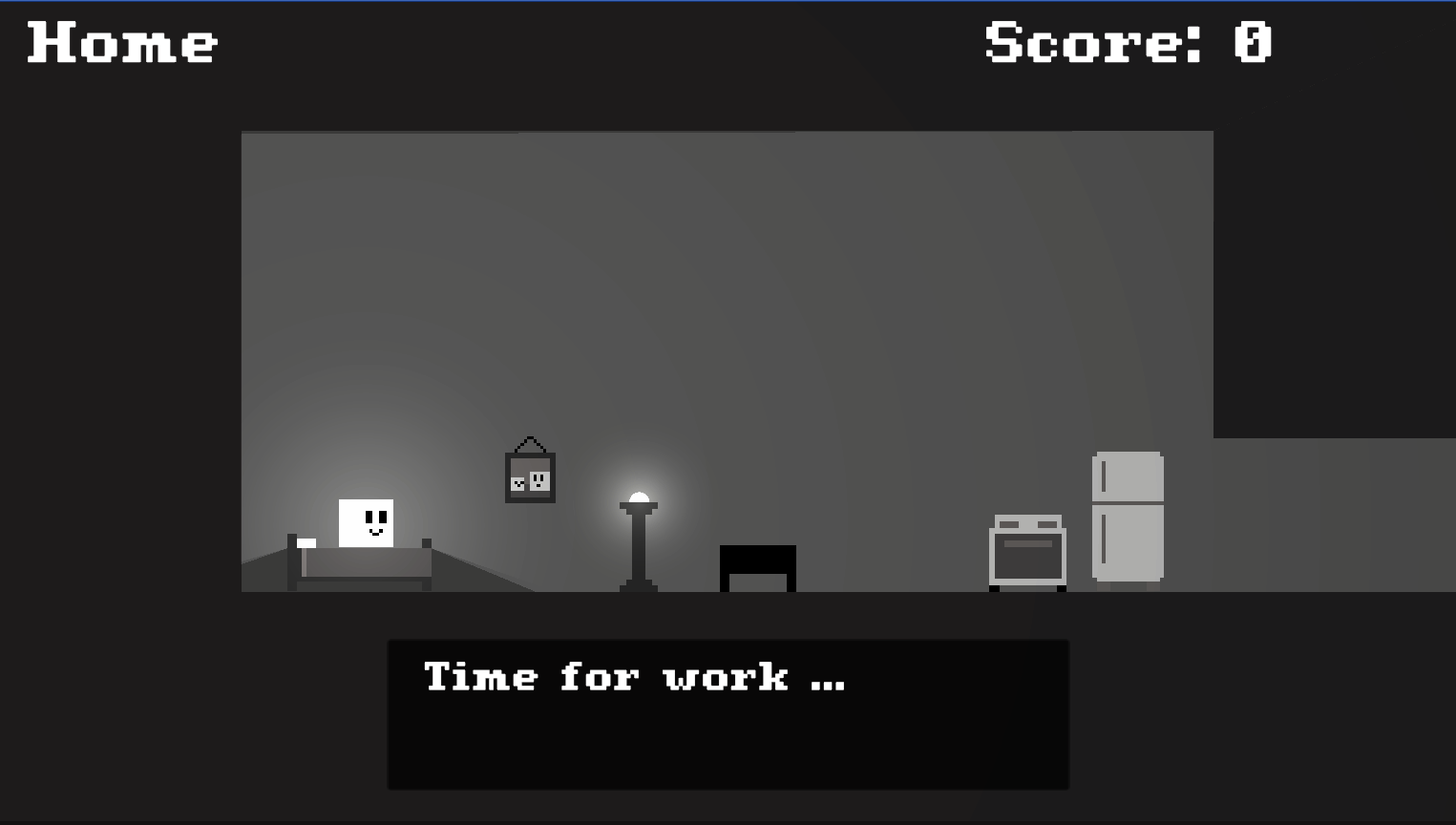

Prismo is a short game, meant to be played in one sitting. Depending on how good at video games the player is, the whole game takes between 15 and 25 minutes to beat. This means a long and complicated story is beyond the scope of the game. Instead, I decided to make the game a short hero's journey tale, leaning into tropes from pop culture. Like in Lethal Weapon, the game takes place the last day before Prismo's retirement. Prismo works in a brick-brekaing factory inspired by the classic Atari game breakout. This story choice helps to cement the '80s arcade aesthetic I was going for when creating the game.

When an evil wizard attacks, Prismo falls (supposedly to his doom) and then has a motivation to complete the game (get back home). Unable to attack, Prismo is an unlikely hero. In spite of this, he's able to make his way through levels and eventually get back to his home.

Aesthetic

Prismo is a simple, monochromatic game with a retro feel. Music is played on an NES synthesizer. Menus and dialogue are in a retro font that hearkens back to an arcade era. Late in the development process, I changed the sound Prismo makes when he jumps to an arcade-sounding 'whoop'. Audio, visuals, and text work together to create a unified feel.

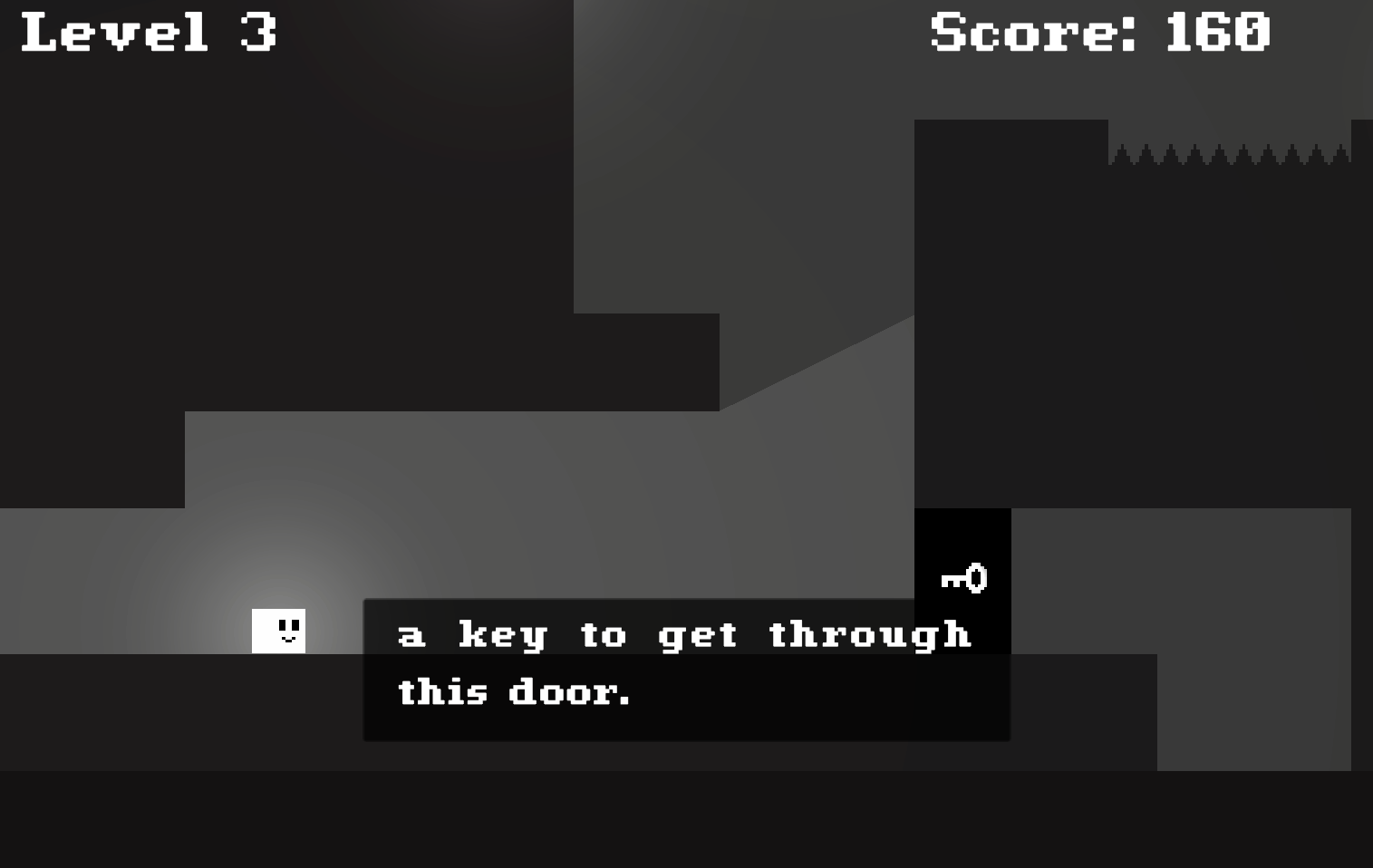

The monochromatic color scheme was meant to be evocative of old white-on-black arcade games like Asteroid. Inspired by that, Prismo has a light that casts shadows. This makes the game visually interesting, and also provided a challenge in designing levels. Because the ground, background, and walls are uniform you can't really tell where Prismo's going in a blank room. While many games fix this with a scrolling background, I didn't want to do that. Instead, pretty much every frame of the game has stationary or shadow-casting objects to help the user feel the relative motion. It was interesting to me how aesthetic choices I made early in the development process influenced level design.

Game Mechanics

2-D platformers have been a standard video game for nearly 50 years. If all Prismo could do was run and jump from flat block to flat block, the game would not be very fun. I tried to add variety to the levels by introducing new mechanics each level. The introduction and Level 1 get the player acclimated to jumping and movement. Level 2 introduces disappearing blocks inspired by the blocks Prismo breaks at work. Level 3 teaches the player to wall jump and has doors that can be unlocked with keys. As the game continues, these aspects add upon each other, and more mechanics are added like cannons, slippery ice, and a propellor hat that lets Prismo fly.

The gradual introduction of mechanics help keep the game fresh without overwhelming the player.

Conclusion

It's amazing to me how making a 15-minute-long game took me hundreds of hours of work over the course of two years. I'm glad I committed to the project and saw it through, in spite of the struggles. Please try Prismo on computer (preferred) or mobile.

I hope you have fun.